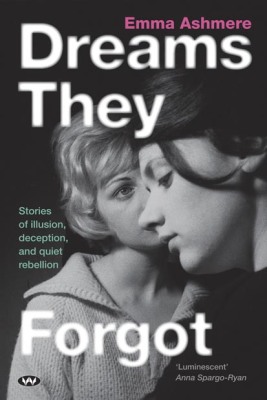

Dreams They Forgot – New Short Story Collection Out Today!

DREAMS THEY FORGOT is out today! Thanks to my publishers Wakefield Press, twenty-three of my stories have been put together in one beautifully designed book.

DREAMS THEY FORGOT is available in paperback and e-book, and is listed on the Sydney Morning Herald’s Books to Read in 2020 and Readings Bookshop Books to Get Excited About and 100 Great Reads by Australian Women 2020: “This debut collection of beautiful short stories spans twenty years of the author’s writing life, bringing together tales of love, loss and feeling out of place.” Read more about it here.

“Ashmere’s prose is precise, almost elusive, reading at times like poetry.” ADAM FORD, July 2020, BOOKS&PUBLISHING.

About DREAMS THEY FORGOT

Two sisters await the tidal wave predicted for 1970s Adelaide after Premier Don Dunstan decriminalises homosexuality. An interstate family drive is complicated by the father’s memory of sighting UFOs. Two women drive from Melbourne to Sydney to see the Harbour Bridge before it’s finished. An isolated family tries to weather climate change as the Doomsday Clock ticks.

Emma Ashmere’s stories explore illusion, deception and acts of quiet rebellion. Diverse characters travel high and low roads through time and place – from a grand 1860s Adelaide music hall to a dilapidated London squat, from a modern Melbourne hospital to the 1950s Maralinga test site, to the 1990s diamond mines of Borneo.

Undercut with longing and unbelonging, absurdity and tragedy, thwarted plans and fortuitous serendipity, each story offers glimpses into the dreams, limitations, gains and losses of fragmented families, loners and lovers, survivors and misfits, as they piece together a place for themselves in the imperfect mosaic of the natural and unnatural world.

Praise for DREAMS THEY FORGOT

“Emma Ashmere’s characters are luminescent. These stories drew me into people and worlds so vivid they practically lived on the page.” — ANNA SPARGO-RYAN, author of The Gulf, and The Paper House.

‘Ashmere’s writing is full of quick insights and telling details. These stories move effortlessly through place and time, entering lives on the point of transgression. It’s an absolute pleasure to travel with them.’ — JENNIFER MILLS, author of Dyschronia, The Rest is Weight, and The Diamond Anchor.

‘Stories of extraordinary range and depth. Deeply engaging and satisfying.’ — PADDY O’REILLY, author of Peripheral Vision, The End of the World, and The Wonders.

‘Ashmere’s prose is precise, almost elusive, reading at times like poetry. It drills down into certain details while leaving others out entirely. This invites the reader to complete the picture by tying together the story elements that Ashmere has chosen to share…The deft description, compelling emotion and insightful observations… will appeal to readers of feminist fiction and Australian realism, in particular fans of Dymphna Cusack or Fiona McGregor.’ — ADAM FORD, BOOKS&PUBLISHING, July 15 2020. (Read the full review here.)

“The stories in this strong and varied collection range across urban and rural Australia and beyond, to such touchstones of Australian travel as Bali and London, and to more exotic settings such as Borneo and regional France. Emma Ashmere’s stories are often impressionistic, never laboriously chewing on their material and trusting the intelligence of the reader to join the dots and grasp the underlying feeling. There are some excellent stories about family life, especially those told from the point of view of a semi-comprehending and bemused child or adolescent. But Ashmere’s greatest strength is in her stories of the historical past, especially in Australia. These stories acknowledge the limits of what is knowable to contemporary readers, evoking instead the unrecoverable strangeness and mystery of the past.” — KERRYN GOLDSWORTHY, SYDNEY MORNING HERALD/AGE, 5 Sep 2020.

“Ashmere moves skillfully and seamlessly between eras and places… this variety is also a strength, making each story feel different from those surrounding it… a thoughtful meditation on the things that can hold you down, and the different ways through.” ELIZABETH FLUX, THE SATURDAY PAPER, 12 Sept 2020.

“These short stories have the compressed clarity of diamonds. From somewhere deep, Ashmere brings these small stories to the surface and sets to crafting them. Every angle and facet is laser cut and polished to perfection. Turn them slowly in your hands. Be dazzled by the light that glances and bounces off their surfaces and be drawn to the shadows that lie within.” JENNY BIRD, BYRON WRITERS FESTIVAL, Sept-Oct 2020 NORTHERLY.

“A short story collection can have much in common with a collection of poetry, where each story pivots on attention to something particular and arresting – an image, a memory, the encounters with strangeness or beauty that can occur in a life. Individual stories build delicately towards such a moment, then fall away quickly, willing a reader to engage with feeling and suggestion rather than the comprehensiveness of narrative…. Dreams They Forgot is subtle and evocative in this way; her stories move both on internal trajectories of revelation and in relation to each other, incrementally building a richly nuanced fabric of story, character, and pinpoints of life experience.” ROSE LUCAS, AUSTRALIAN BOOK REVIEW, 29 Nov 2020.

“Generally, an author’s work improves with time, but all twenty-three stories in Dreams They Forgot are of equal quality. In some collections, stories can blur together, but the diverse locations and historical periods utilised in these stories make each piece memorable.” ANNIE CONDON, READINGS MONTHLY, Sept 2020.

“This is an exquisite collection of short stories. Many have a filmic quality as Ashmere introduces a scene and moves like a camera would, resting on an object or a person, and then revealing subtle nuances in gestures or words as we are led further in. The language has the expressiveness of poetry, creating pictures and interactions, leading into stories that leave us pondering long afterwards…. the stories can be read and enjoyed time and again. Highly recommended.” HELEN EDDY, READPLUS, 17 Nov 2020.

“Emma Ashmere’s short story collection, Dreams They Forgot, is creatively atmospheric, a series of ‘slice of life’ vignettes set in a variety of eras with a mostly feminist leaning. Emma writes with sublime texture, so much simmering beneath the surface. ” THERESA SMITH, THERESA SMITH WRITES, 25 Sep 2020.

“Ashmere has curated this collection in a way which makes it read almost like a novel… Many characters seem to be echoes of each other (or maybe the same person?)… Her prose sits lightly on the page, remaining poetic without forgoing narrative drive. Like a caricaturist, she can evoke a full person with just a few strokes of the pen… If you are yet to discover the short story, then this collection might just persuade you. And if you are already a convert, then Ashmere will no doubt delight and engage.” TRACEY KORSTEN, GLAM ADELAIDE, 25 Nov 2020.

The COVER

The photograph ‘Lynne and Carol, 1962’ is by the late Melbourne photographer Sue Ford. See more of her stunning work archived here. My thanks to the estate of Sue Ford for kindly granting permission to use her work.

Behind The Book

Q&A with the Feminist Writers Festival about writing Dreams They Forgot.

‘Written on Water’ published in Overland about writing the story ‘The Second Wave’ about the 1976 ‘tidal wave’ predicted to wipe out ‘the sinners’ of Adelaide.

‘What I’m Reading’ on reading Ali Smith’s new novel ‘Summer’ is on Meanjin’s blog.

‘Catch A Passing Thought’ on writing short stories and Dreams They Forgot.

Author Talk with Theresa Smith Writes.

Chatting to Pamela Cook and Kel Butler on the W4W podcast.

Hear Emma read her story ‘The Sketchers’ inspired by the art of Grace Cossington Smith and commissioned by the National Gallery of Victoria’s NGVmagazine.

Events

Join authors Pip Williams, Victoria Purman and Emma Ashmere for Down the Rabbit Hole: Talking History hosted by History South Australia 20th April 5.30pm (Adelaide time). Free zoom.

Launch with Nikki Anderson for Feast LGBTQI Festival 2020.

Launch with Nikki Anderson for Feast LGBTQI Festival 2020.

Thurs 24 Sept 6.30pm (Melbourne time): ” Women Who Break The Rules” Online Event Readings Bookshop. Join Emma Ashmere (Dreams They Forgot) and Laura Elvery (Ordinary Matter) talking to publisher/editor Jo Case about their new short story collections. Free zoom event – but you need to register.

Where To Buy

Find DREAMS THEY FORGOT (RRP AUD $24.95) at your local bookshop or online:

Wakefield Press (Adelaide)

Abbey’s Bookshop (Sydney)

Avid Reader (Brisbane)

Bookroom at Byron (Northern NSW)

Booktopia (Online)

Gleebooks (Sydney)

Readings (Melbourne)

Imprints Bookshop (Adelaide)

Jeffrey’s Books (Melbourne)

Lismore Book Warehouse (Northern NSW)

Matilda Bookshop (Adelaide Hills)

National Library (Canberra)

Ravens Parlour (Barossa Valley)

Riverbend Books (Brisbane)

Wheelers Books (Online)

Dymocks Books (Online)

*Also e-book available. Please note – the RRP is AUD$24.95. Prices vary on Book Depository, Fishpond, Amazon etc.*

***

See more posts about reading and writing short fictions and creating a short story collection.

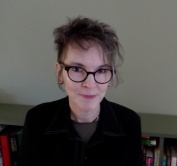

About The Author

Emma Ashmere was born in Adelaide, South Australia. Her new short story collection DREAMS THEY FORGOT is published by Wakefield Press, and follows her critically acclaimed debut novel, The Floating Garden which was shortlisted for the Small Press Network MUBA/Book of the Year 2016. Her stories have been widely published including in the Age, Griffith Review, Overland, Review of Australian Fiction, Sleepers Almanac, Etchings, Spineless Wonders, #8WordStory, NGVmagazine, and the Commonwealth Writers literary magazine, adda. She was shortlisted for the 2019 Commonwealth Writers Short Story Award, 2019 Newcastle Short Story Award, 2018 Overland NUW Fair Australia Prize, and the 2001 Age Short Story Competition; and longlisted for the 2020 Big Issue Fiction Edition, and the 2020 Heroines Prize, with another in the NZ/Aust Scorchers climate change anthology.

Yesterday in Byron Bay, the wild surf crashed and the winter sun flickered. In an upstairs room off main street, a dozen or so keen writers hunched over their notepads writing Flash Fiction. The workshop was timed to coincide with the inaugural

Yesterday in Byron Bay, the wild surf crashed and the winter sun flickered. In an upstairs room off main street, a dozen or so keen writers hunched over their notepads writing Flash Fiction. The workshop was timed to coincide with the inaugural